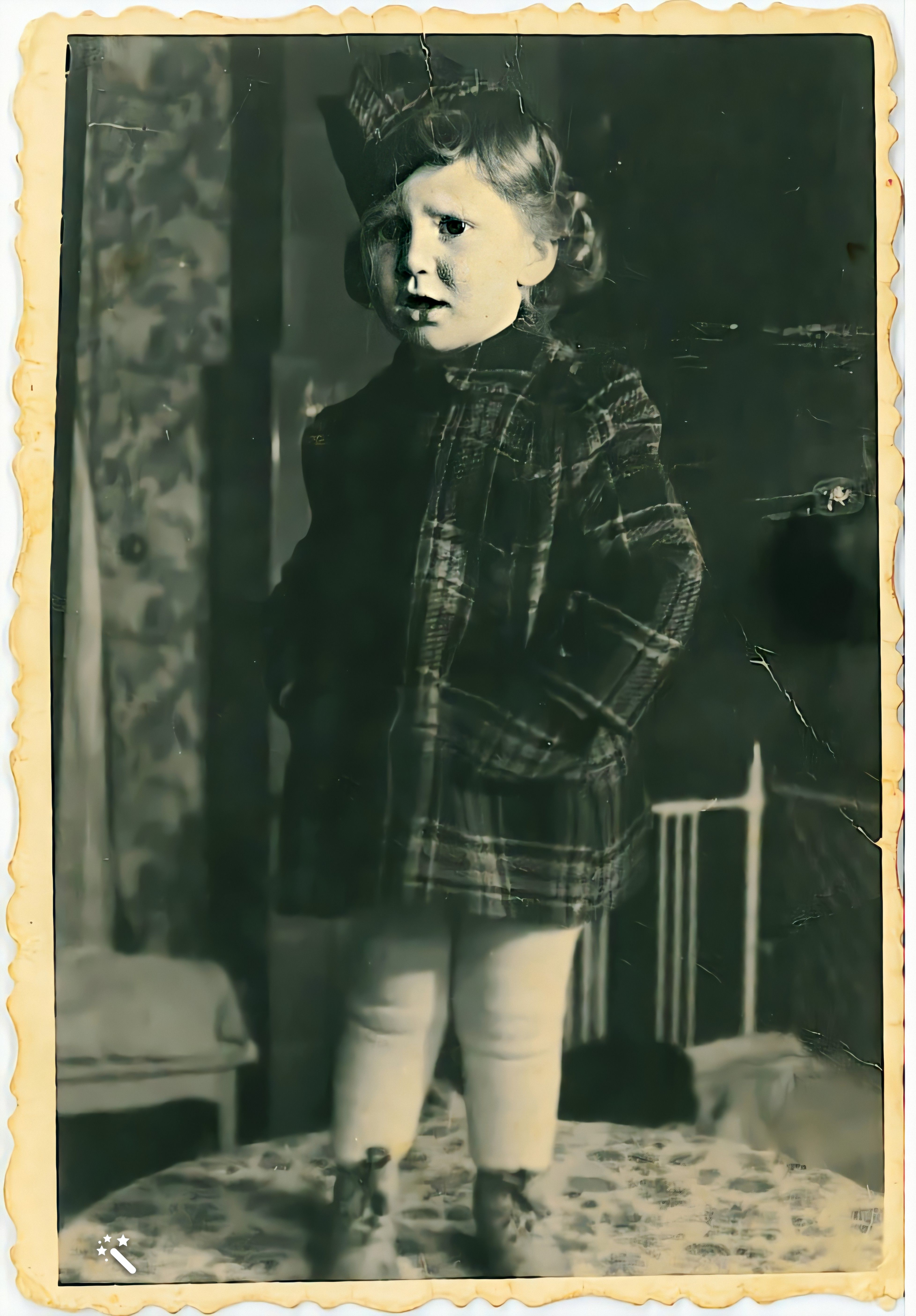

Relli was born in Warsaw on March 11, 1939, the only child of Franka née Presendikt and Michael (Michal) Glovinsky. The name "Relli" is unique, deriving from the name of her grandmother Rachel Luchi. Relli's mother took the initial letters of "Rachel" and "Luchi", and her father added the sound of the Hebrew letter "yod" which, as a suffix, means "mine". Relli's family was educated – Polish, Russian and German were spoken at home – and their home was traditionally Jewish.

When the Warsaw Ghetto was established, the family was imprisoned there together with Relli's maternal grandfather, David. Relli says: "Except for me, no one from my mother's family survived the Holocaust. Everyone perished. However, on my father's side, the story is different. My father was the eldest of five brothers. Most of my father's family immigrated to Palestine-the Land of Israel in the 1920s and 1930s, but because my father was a businessman, he remained in Poland where most of his business was in Danzig (Gdansk). He lived there until 1938, but my father was a huge lover of Israel and he made sure to financially support his pioneering family who had immigrated to Eretz Israel. From 1939, my father started working in the ghetto as a forced laborer. Because of his experience as a textile merchant, he worked in a factory that made German military uniforms. The owner of the factory was a man named Schultz. Unfortunately" says Relli, "I remember almost nothing from my time in the Warsaw Ghetto. I think the reason is that I was too small or it was some kind of repression mechanism I created or, alternatively, because my parents tried very hard to protect me. I don't remember that I felt any danger there."

She continues: "My story begins in January 1943, on the eve of the outbreak of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, when the Jews realized that the ghetto was going to be liquidated and all the Jews that were left would be sent to the extermination camps. We already knew what happened to those sent on transports: there were rumors all over the ghetto. My parents understood that because my father worked for the Nazis in a vital factory, they would not be deported to the extermination camps with the rest of the Jews but they would be sent for relocation along with all the factory workers. The new labor camp was the Trawniki camp. Unfortunately, in the end this camp, too, was liquidated.

There was a massacre in Trawniki on November 3, 1943. All the factory workers and others who were in the camp, about 10,000 people, including my parents and grandfather, were shot into the killing pits and then burned. This massacre was called 'Operation Harvest Festival' by Heinrich Himmler. So, my parents had understood the imminent danger and they also had understood that they were almost certainly going to be murdered. Their great concern was me, their only child. How would they manage to save me?"

Relli explains, "The sooner they acted, the better it would be. They decided that even before moving to the Trawniki camp, they needed to find a solution. At this point, I want to add that I always claim that I've had a lot of good luck in my life. That was the first time I realized it. Next door to my parents in the Warsaw Ghetto, lived the Meltz family. The father of the family was Alexander. He and his wife had a daughter who was a year older than me. Alexander was a Jewish communist who had been a member of the Communist Party before the war. And so, it turned out that even during the war, his Polish party fellow members did not forget him but kept in touch with him to offer him and his family – with the help of the Polish resistance – a plan of escape from the ghetto and for concealment in Aryan Warsaw. I met Mr. Alexander in Israel in 1975. He was the one who revealed to me for the first time the full story behind my connection with the Abramowitz family.

The person who was supposed to carry out the plan was a Polish man named Jozef Abramowitz. The plan was that after being smuggled out (of the ghetto), Alexander Maltz would hide in Jozef Abramovitz's workshop. Alexander's wife would hide elsewhere in Warsaw and their baby girl would be hidden in the house of Jozef Abramovitz and his wife Janina. The Abramowitz couple had no children, so they planned to represent the little girl as their daughter if necessary, but just before the plan could be implemented, circumstances changed. The caregiver who worked for Alexander Maltz said that she would take Alexander's wife and their little daughter and hide both of them with her. To my sorrow, his wife and daughter and the caregiver were informed upon and murdered while hiding.

That solution would have been better for Alexander because his wife would have been able to take care of their daughter. And so, it turned out that the Abramowitz couple had the opportunity to hide another little girl with them. Alexander, my parents' neighbor and friend, explained to them that there was a way to save me. My mother was afraid to flee the ghetto with my father because she did not want to leave my grandfather behind. My grandfather was too old to run away. But she realized that this was the best chance to save me and after long deliberations with my father, they decided to hand me over to Mr. Maltz, to get me out of the ghetto.

That evening, my parents put me to bed so I would not suspect anything and cry. In the middle of the night, Jozef Abramowitz came and put me in a sack and took me out of the ghetto. If you ask me, to this day, I do not know which routes he took into and out of the ghetto, but it's clear that he had (his ways). He entered (the ghetto) countless times. Sometimes, he smuggled in weapons for the revolt and he even managed to save more Jews and help them flee. Jozef was simply an extraordinary man, "Righteous among the Nations" in the full sense of the words!

And so, one morning when I was three, I woke up where I had been sleeping on three chairs. The chairs had been pushed up against a wardrobe as a kind of makeshift bed. I remember it so clearly: They had a one-room apartment which was built in such a way that the bed of the Abramowitz couple was in the living room. Next to the bed, there was a small curtain that separated the 'bedroom' from the kitchen. The bathroom was not in the house at all. If you had to go to the bathroom, you had to go out to the stairwell. And because the apartment was so small, there was no room to set up another bed, so I slept for many more months on those chairs. My whole life, this has been food for thought for me, because the Abramowitz couple were people who had no means and possessed almost nothing. It was even more amazing that they took this nothing and made it everything. They chose to give from what they did not have. They saved me and thanks to them, I'm alive.

When I woke up, I remember being a bit shocked. I saw two strangers standing next to me. They told me 'Good morning'. I asked them, 'Where are Mommy, Daddy and Grandpa'? And they answered me, 'Your mother, father and grandfather gave you to us so that we could take care of you'. At that moment, I did not cry or shout, but I asked them again for my father and mother. Mr. Abramowitz picked me up and made me something to eat (a hard-boiled egg; I remember the smell to this day). And his wife Janina told me that from now on I should call them Daddy and Mommy and they would call me Lala ('doll' in Polish). I really didn't want to cooperate, but they told me I must. 'And it must be our secret that you are not really our daughter and no one should know about it.' They explained to me that it was a kind of game played between us, a kind of pretend, 'because we have no children, you will be our doll'.

Then Mrs. Abramowitz took me to the wardrobe and showed me three exceptional furs that my mother had left with her, and she told me: 'You see that your mother left her precious furs here and she will come to pick them up, so she will come to pick you up, too.' At that moment, I was convinced. It made sense to a four-year-old girl. In addition to the furs, my mother also left with the Abramowitz couple a book of fairy tales that I really liked. Every time it was read to me or I looked through this book, it helped calm me. Of course, I missed my parents very much. I wanted to see them come back and take me home with them. Unfortunately, that did not happen.

But I did have a kind of farewell with them. Right before they were deported to the Trawniki camp, what happened was pretty much like this: the Abramowitz family lived just outside the ghetto at 6 Krochmalna Street. Very famously, in Warsaw in 1939, the street was divided where the ghetto wall crossed it. At the end of the street, inside the ghetto, was Janusz Korczak's orphanage. One night, Mr. Abramowitz managed to smuggle my parents beyond the ghetto wall (as I've mentioned, they did not want to flee altogether because of my grandfather). I remember that night. I was woken up and suddenly I saw three figures in front of me. I immediately recognized that it was my parents and wanted to shout with joy, but my father made a sign for me to be quiet and even though I was little, I controlled myself. My mother sat on the Abramowitz couple's bed and took me on her lap. She told me that she loved me very much. Then my father came and took me in his arms. I remember that all I had to say to my father was, 'Daddy, who brings you your slippers now?' (Today, I know that it was actually my way of saying, 'Don't you miss me? Look, I can be useful. I miss you. Take me back!' My father put me down and they put me back in bed. In the morning, I woke up and they were gone.

After the war, while I was growing up, for many years I thought that that was just a childish dream in my memory, a sweet memory I chose to imagine but not something that had really happened. In 1984, I went to Poland for the first time with a delegation from the Ghetto Fighters' Museum. I met with Janina's sister and her husband Stefan, in Warsaw. By then, Janina and Jozef had already died. Stefan told me: 'You know, we met your parents during the war. Just before they were deported from the Warsaw Ghetto, Jozef managed to smuggle your parents out and bring them (to his place) to say goodbye to you', and I answered him: 'What, really?' Then he told me that I had been very small and probably couldn't remember it. And then I told him what I had said to my father about the slippers. He was completely amazed. He told me it was true, and he said: 'Everyone who was in the room couldn't stop crying after you said that'. To my sorrow, my parents never came back to me but at least I realized I really had been saying goodbye to them and I hadn't imagined that.

When I lived with Jozef and Janina, the rules were that I was not allowed to go out at all and certainly not to open the door to anyone. I used to look out the window. I was so jealous of the children playing in the yard, but I was a very good girl and obeyed instructions. Staying in hiding with the Abramowitz family went pretty well for me except for four exceptions:

The first case was when one day, when Nina left the house, she locked the door and warned me that under no circumstances should I open the door. I was looking for something to do and started playing with yellow dust cloths. I created a pretend dress. Time passed and I got bored. Suddenly, I saw a box of candies. I took the box and for the first time I opened the window of the apartment. Jozef and Janina's apartment was on the ground floor, open to the yard where children would play. And I started asking the kids playing outside 'Who wants candy?' and I threw some candy out to them. Some kids came and took candy. One of the girls asked me if I wanted to play outside with them, too. I answered 'Yes', and because I was very small and light, one of the older kids stood a box under the window and simply lifted me out. It was so much fun! We played hide and seek and jumped rope and so on. While I was playing outside, Janina came back home. She was so scared (when) she saw me outside playing with the other children (but) she realized that if she forcibly pulled me inside, that would create a very dangerous situation for me, so she came and told me, without any shouting, 'Honey, come in the house. You don't have a sweater and it's very cold.' When we went in, she really explained to me for the first time why I wasn't allowed to go out and how dangerous it was for me, and thank God the story ended miraculously without anyone knowing (the truth).

The second case was much scarier. A piano teacher lived above us on the third floor. She, too, was an amazing woman and she also hid Jews in her house, a boy of ten and a girl of six. Sometimes Janina would give me permission and I would quietly go upstairs to play with them. I would also try to play the piano, but very quickly I realized I had no talent for it. One day, when I left the piano teacher's apartment and went back to our apartment, it was very quiet even though I knew that Janina was in the house. The second I went in, the door closed behind me and suddenly I saw Janina tied on the floor with a man training his weapon on her. Another man was turning the house upside down as if he were looking for something, and the third man had closed the door behind me. The oldest of them was watching what was happening. I turned to the older man and started shouting, 'What are you doing to my mother?" He asked me, 'Who are you?' And I told him, 'I'm Lala'. At that moment, I heard the man in charge say to the others, 'We're not having anything to do with children.' And they just left. To this day, I have no idea who they were or what they wanted. I just understood that they were bad people. Nor did Janina tell me anything afterwards. But what had happened really scared me. That same day, Janina and I went to her sister's house to calm down after that experience.

Shortly after that incident, the third event occurred. I continued to go up to the piano teacher's apartment to play with the kids who were hidden with her. I really liked that I finally had friends. We also had a kind of a secret knock on the door that would tell them it was me coming. One day, I went up as usual to play with them and I knocked on the door with the agreed-upon knock but no one answered me. I knocked again and again until finally I opened the door. To my surprise, it was not locked. When I entered, I saw a terrible sight: everyone was lying dead on the floor. To this day, I don't know what happened. I ran downstairs fast. I told Janina. Janina took me to her sister's that day and we never talked about it again.

But all those events were just a warm-up for the fourth, when I felt the danger. That event took place during the winter. I had caught a cold and was very sick until Janina decided to take me to the doctor. Janina wasn't afraid to be seen with me outside (since) I looked completely Polish: blonde with blue eyes. And so, on our way to the clinic, we got on the tram. At the time, the tram was divided into two carriages. The first carriage was reserved for Germans (according to the Aryan supremacy laws). Poles could only ride in the second carriage. And when the tram stopped, a Nazi officer sitting inside the first car saw Janina waiting with me. The Nazi officer turned to Janina and said to her 'What a cute girl you have. It's too bad she has to stand in line. Hand her to me. She'll sit with me in the car and when you arrive I'll give her back to you.' Janina was in a very difficult situation. She could not say no, because then the officer would become suspicious but on the other hand, she knew that if she said 'yes' there was a chance I would say something that would endanger us (I was still quite small). Janina handed me to the officer but before that, I remember she shook my hand very hard as if she were warning me. And then she added, 'Be a good girl. I'm giving you to the officer just for the ride and at the nearest station, I will come to collect you'. Janina got in the carriage for Poles. Meanwhile, I sat on the officer's lap. He was very nice and gave me chocolate and at the next stop – of course, out of fear we didn't go to the clinic in the end – when Janina came to pick me up, he told her that I was well-educated and that I reminded him of his daughter. When we left, I told Janina that I didn't tell him anything.

Following those four events, it was decided that Janina and I needed to leave Warsaw. The Abramowitz family had close friends who owned a mansion in Lublin. The estate was called 'Vishnofka'--'Cherry' (because) the mansion was next to some cherry trees. We actually went there. The mansion itself had two floors. The owners – the friends of the Abramowitzes – lived on the first floor. The second floor was the headquarters of the German army. We lived in the attic. The cover story was that we had fled Warsaw because of the harsh wartime conditions that prevailed there. We stayed at that place until the spring of 1944 when the Russians wrested Poland from the Germans.

Janina, who was very worried about her husband, wanted to return to Warsaw to see how he was and because she knew Russian, she offered to work as an interpreter for the Red Army. Initially, she agreed to take me with her and so we started the journey together, back towards Warsaw, but because of the difficult situation on the roads and because I became ill on the way, she left me in one of the villages we passed. She just went into one of the huts and asked one of the families (for a fee, of course), to take care of me until she came back to pick me up. The family agreed. They were a family of farmers: father, mother and ten children. Of course, they thought I was Polish. I remember I really liked to sit with the farmer's wife and tell her the stories from my book. She really enjoyed it. While I was with them, with much help from one of the children who was in first grade at the time, I was able to teach myself to read independently. I would just listen to him and learn from him. Luckily, I have good study skills. The family was a pious Christian family and I remember going to church with them on Sundays. Overall, I had a pretty pleasant time there.

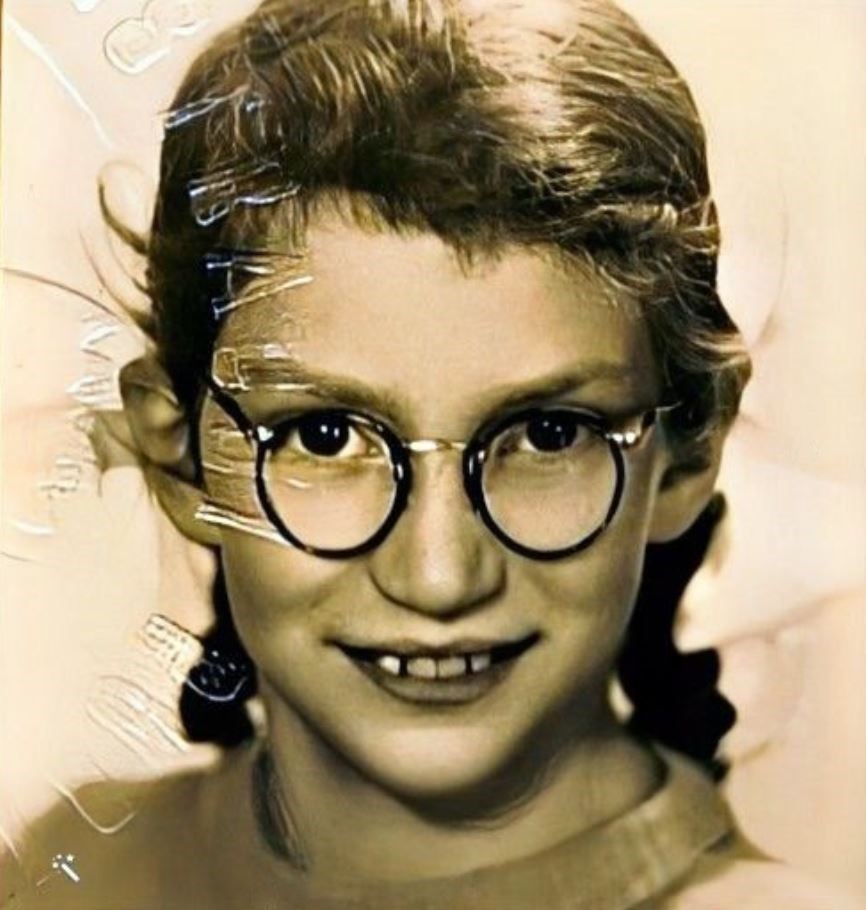

When the war ended in May 1945 and Janina and Jozef came to pick me up, the first thing the farmer's wife told them was that while I was with them I had learned how to read. Jozef did not believe it. He thought I just remembered the stories by heart, so he took out a newspaper and let me read. I did read and he was shocked. So when we got back to Warsaw, Janina and Jozef decided to send me to school, and because I already knew how to read, I started school in the second grade on a trial basis, despite the fact that I was only six years old.

As I mentioned at the beginning, my father was the only one in his family who didn't leave Poland. My father's whole family immigrated to Eretz Israel before the war. They knew nothing about what happened in Europe. In October 1945, one of the refugees arrived in Eretz Israel and once, when he sat with his friend in a coffee house ("Atara", in Tel Aviv), they talked quite loudly about what had happened during the war and suddenly in the middle of the conversation the refugee turned to his friend and told him that he must find the Glovinsky family. And he told his friend about me and my situation and that I was living in Warsaw with the Abramowitz family who had saved me, but it was time for me to return to my own family. His friend told him he didn't know the family but, of course, when talking in a cafe everyone listens. Suddenly, someone touched the refugee's shoulder and told him, 'Sorry, I overheard your conversation, but the person you are looking for, Haim Glovinsky, is a very close friend of mine. And that was how my uncle learned that I was alive and that he would have to arrange to bring me to Israel. But how could that be done?

Janina and Jozef also tried to find my family in Eretz Israel to tell them I was alive, so they wrote a letter to my uncle (Haim Glovinsky) in which they told him about me. My Uncle Haim was a pretty famous person in Tel Aviv, one of the founders of the Football Association, and so he actually learned that I was alive from two different sources at the same time. My uncle asked "the coordination organization" that was located in Lodz to help bring me to Eretz Israel, but there was a snag: the Abramowitz family responded asking for money for 'my release'. I think that was because they had gotten used to having a daughter and did not want to give me up. In addition, the Polish court sided with the Abramowitz family and left me legally in their custody, so the coordination organization contacted my uncle and said that the only chance to release me would be if he came to Poland and tried to present my case in court.

At that time, my Uncle Haim went to the United States with Hapoel Tel Aviv as part of a friendly game. During his stay in the United States, he managed to get a visa to Poland, but even this attempt was not successful and I remained in Poland, to grow up there. In the summer of 1949, my stepmother Janina died suddenly. She had fallen at home, causing a brain hemorrhage. Jozef quickly remarried. His second wife wanted very much to marry him but imposed one condition: she did not want to raise that "Jewish girl", me. So, Jozef decided to rent his spacious apartment to a Polish family, in order to produce extra income and we moved to a small apartment. I was only allowed to sleep in the apartment at night. They put my bed in the entrance hall. The new wife enrolled me in a communist school, a terrible school with a long school day. I had nowhere to return to at the end of the day (and) I would wander the streets. Every now and then, I would go to Janina's sister. I would come home late at night just to sleep. I was a kind of abandoned girl.

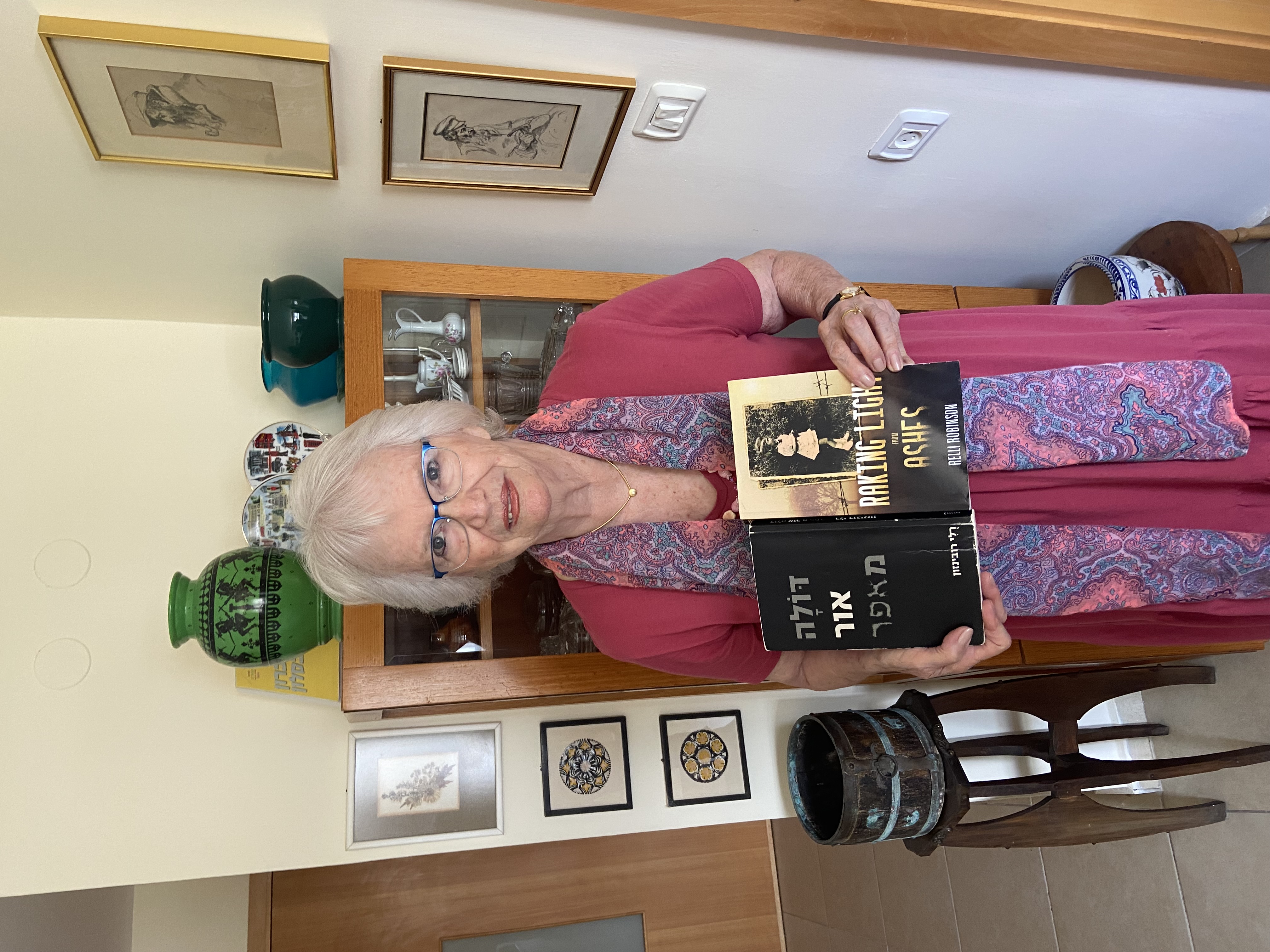

Luckily, everything changed in 1949 when a woman from Haifa – Tzipora Nesher – was hired by the Israel Foreign Ministry to work at the Israeli embassy in Warsaw. Tzipora knew my aunt, and she was told about my situation in Poland. She said she would take on the case as a personal project and so she did, when she started her job in Warsaw. With a lot of help from the Israeli ambassador Israel Barzilai and after very long negotiations and a trial (because under Polish law I was an adopted child), they managed to bring me to Israel. The legal process took about a year and so, in October 1950 I arrived in Israel. In Israel, I grew up in Pardess Hanna. My Aunt Rita and her husband Abraham Robinson adopted me. I entered the sixth grade and later attended the Green Village Agricultural High School. Abraham Robinson was one of seven brothers. One of his brothers, Professor Nathan Robinson (the man who invented the solar water heater), would become my father-in-law. I married his son David in 1962. David died in 2011. We have two children, Michal and Nativ, and six grandchildren.